Antarctic Region

Things to DO

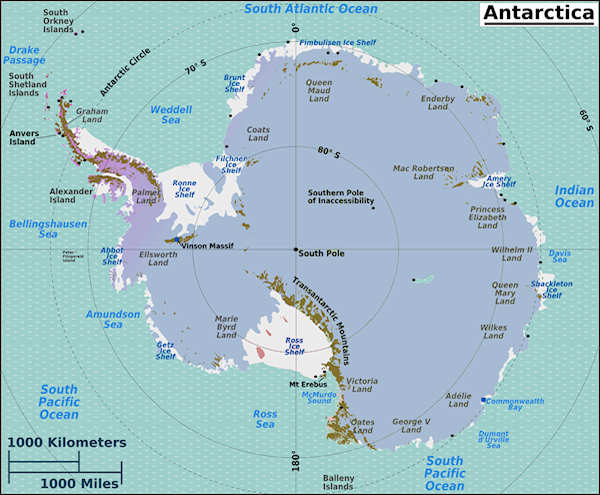

Antarctica

Discovering Antarctia

|

|||||

Belief in the existence of a Terra Australis – a vast continent in the far south of the globe

to "balance" the northern lands of Europe, Asia and North Africa – has existed since the times of

Ptolemy (1st century AD), who suggested the idea to preserve the symmetry of all known landmasses

in the world.

European maps continued to show this hypothetical land until Captain James Cook's ships,

HMS Resolution and Adventure, crossed the Antarctic Circle on 17 January 1773, in

December 1773 and again in January 1774. Cook in fact came within about 75 miles (121 km) of the

Antarctic coast before retreating in the face of field ice in January 1773.

The first person who set foot on Antarctica is said to be the American John Davis, a sealer,

who landed there on 7 February 1821.

James Weddell made three voyages to the Antarctic between 1821 and 1824, in his brig, the

Jane, exploring South Georgia, the South Shetland and the South Orkney Islands , and the ice

around Antarctica. On his third voyage, he sailed down into what is now the Weddell Sea, achieving

a southern latitude of 74° 15’ on February 20, 1823, a record that would not be surpassed for almost

eighteen years.

In 1840, Charles Wilkes, leader of an American Navy expedition, was the first to cross a

substantial swath of land and realize that the new island was a continent rather than just a large

island.

|

|||||

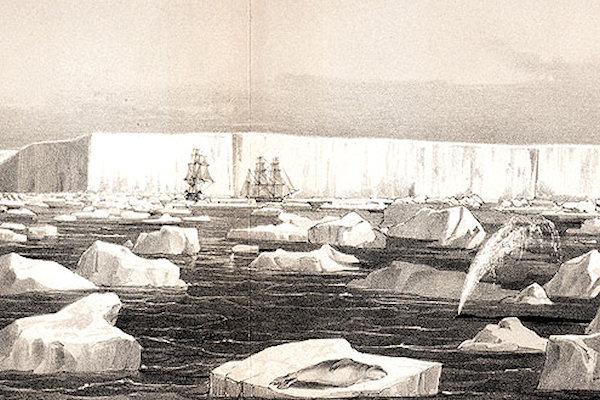

The British were beaten out of the starting gate by both the French and the Americans, but they recovered

quickly, and by 1839 they had their own expedition ready to seek the south magnetic pole. The ships were

the Erebus and Terror, and the commander, fittingly, was James Clark Ross, who had

discovered the north magnetic pole in 1831. The sturdy ships managed to penetrate a very dense ice pack,

and in January 1841, Ross sighted land, which he called Victoria Land, a part of Antarctica that

lies along what is now the Ross Sea. He was surprised to see a volcano on an island in active

eruption. He named the active volcano Mt. Erebus. But the greatest surprise of all was the

discovery of a stupendous ice sheet, nearly 200 feet high and extending for hundreds of miles. This was

the Ross Ice Shelf, the largest floating ice sheet in the world.

Ernest Shackleton, led the Nimrod-expedition (1907 - 1909), in an effort to be the first to reach

the South Pole, and was only 180 km away before they had to turn back. Parties from that expedition were

the first to discover the Magnetic South Pole, however.

After the magnetic south was discovered, the competition really got intense. Robert Falcon Scott,

the Brit, and Roald Amundsen, from Norway, sailed their ships Terra Nova and Fram

in an effort to be the first to the South Pole. Their expeditions took place throughout the year 1911 and

early 1912. Roald Amundsen's party was first, reaching the South Pole on 14 December 1911. Their strategy

involved taking 52 dogs with them and feeding the dogs to the others as they died. They returned with only

11, as this is how these expeditions were done in those days. Robert Scott reached the South Pole only a

month later, but his party of five perished on the return trip across the Ross Ice Shelf. Today the

Scott-Admundsen South Pole Station is named in honor of the two men.

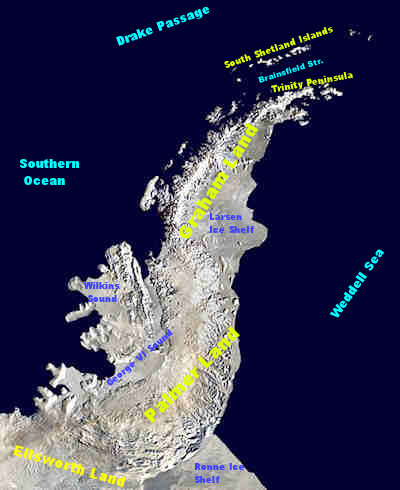

Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula is the northernmost part of the mainland of Antarctica, lying North off Ellssworth

Land and containing Graham Land in the North and Palmer Land in the South.

As, beeing the mildest and most accessible part of the continent, the Peninsula gets tens of thousands of

people every year; a;most half of them visit the very sampe places. Ship captains and expedition leaders

instinctivel reach for these favorite dozen sites because they are known safe anchorages offering convenient

acces to penguin rookeries, research stations or historic sites, all within a manageable distance of one

another.

The first sighting of Antarctic Peninsula is disputed but apparently occurred in 1820. The most likely first

sighting of the Antarctic mainland, was probably during an expedition of the Russian Imperial Navy that was

captained by Thaddeus von Bellinghausen. The party did not recognise - what they thought was an icefield

covered by small hillocks - as the mainland on 27 January 1820.

Edward Bransfield and William Smith were the first to chart a part of the Antarctic Peninsula

- just three days later - on the 30 January 1820. The location was later to be called Trinity Peninsula,

the extreme northeast portion of the peninsula.

The next confirmed sighting was by John Biscoe who named the northern part of the Antarctic Peninsula,

Graham Land, in 1832.

The first to make landing on the continent is also disputed. A 19th century seal hunter called John

Davis was almost certainly the first, however sealers were secretive about their movements and their ship

logs were deliberately unreliable, in order to protect any new sealing grounds from competition.

Between 1901 and 1904, Otto Nordenskiöld led the Swedish Antarctic Expedition, one of the first

expeditions that was to explore parts of Antarctica. They landed on the Antarctic Peninsula in February 1902,

aboard the Antarctica which later sank not far from the Peninsula with all crew saved.

The British Graham Land Expedition between 1934 and 1937 carried out aerial surveys and concluded that

Graham Land was not an archipelago but was a Peninsula.

Drake Passage

The Drake Passage is the body of water between the southern tip of South America at Cape Horn

(Chile) and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean

(Scotia Sea) with the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean and extends into the Southern Ocean.

The passage is named after the 16th century English pirate Sir Francis Drake. Drake's only remaining

ship, after having passed through the Strait of Magellan, was blown far South in September of 1578. This

incident implied an open connection between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

The first recorded voyage through the passage was that of the Eendracht, captained by the Dutch navigator

Willem Schouten in 1616, naming Cape Horn in the process.

The Drake passage is known as the roughest ocean in the world. Satellite images show a cyclonic low of

basically hurricane strength travels through the Drake Passage on the average of once every three weeks.

Crossing the Passage

March 2011

|

|||||

Waking up the first morning, i found that the sun was shining and the sea was flat calm. The Drake Passage

has a fearsome reputation for being stormy but King Neptune was treating us very gently!

The first picture's this morning was Southern Royal Albatros.

The albatross family is closely related to other families of seabird, which collectively are known as

tubenoses. These birds are highly adapted to a life at sea and have a special mechanism in the heads

which, together with the kidneys, excrete salt from the body. Many tubenoses also have a highly developed sense

of smell, which helps in their wide-ranging search for food.

The second day, we continued southwards towards the South Shetland Islands and the distant Antarctic

Peninsula but there was a quite hard wind from east-northeast and it was snowing a lot.

Hopefully, we can have some nice weather at the Peninsula.

Trinity Peninsula

Trinity Peninsula is the extreme northern portion of the Antarctic Peninsula, extending

northeastward for about 130 km (80 miles) from a line connecting Cape Kjellman and Cape Longing.

Dating back more than a century, chartmakers used various names

(Trinity Land, Palmer Land, Land of Louis Philippe) for this portion of the Antarctic peninsula,

each name having some historical merit.

The recommended name derives from "Trinity Land" given by Edward Bransfield during January 1820

(for the Trinity Board), although the precise application by him has not been identified with certainty

and is a matter of different interpretation by Antarctic historians.

Visiting The Peninsula

March 2011

|

|||||

The wake-up call at 7 a.m. met us with tales of Antarctic Autumn Conditions as we approached the

Antarctic Sound.

A fierce wind at 30-40 knots from the Weddell Sea and a temperature of -9° C ruled outside!

Spray blown off the sea had covered the Plancius from bow to stern with ice and it blocked the views from the

lounge windows. It was even so cold that there was ice on the inside of the metal window frames.

Crew members set to work, hammering off crusts of new ice in strategic places.

The surface of the sea was rough but the waves were relatively small, dampened by large patches of sea ice and

quite a few mid-sized to giant icebergs drifting off from the mainland, their characteristic side walls carved

out by metre-sized slabs of falling blocks.

With the wind-speed increasing to around 50 knots in the mid-afternoon and the outside temperature dropping

to -12° C we had no choice but to stay at sea and stay on the ship.

For the comfort off he passengers, the captain decided to seek shelter at the leeside of the Peninsula,

crusing up and down in the Brainsfield Street.

|

|||||

Te next day, unfortunately, the hoped-for improvement to the weather had not materialised.

On the contrary, conditions had worsened!

After a slight drop at 04.40 hrs, the wind had freshened to 55 knots, gusting 66 to over 70 during the

morning.

At least the temperature had improved to minus seven degrees Centigrade.

Nevertheless, because of the buffeting wind and icy decks covered with frozen sea spray, everyone

was instructed to stay inside.

In the early hours of the last day, the wind finally subsided and the Captain decided to head north

towards South Georgia. Our departure was 12 hours late but the Captain informed us that he could

catch up on time in the next three days.

First the Plancius moved slowly as there was still a large swell running from the east, poor visibility and

ice around. Later in the morning the Captain was happy to see only clear, open water and good visibility, thus

allowing him tom gain up some time.

At last, we left Antarctica but with a lot off mixed feelings; seeing quite a lot off sealife (specialy

snow-petrelds), but with not a glimpse of the Peninsula, meaning, some day, i have to come back.

Scotia Sea

Habitually stormy and cold, the Scotia Sea is the area of water between Tierra del Fuego,

South Georgia, South Sandwich Islands, South Orkney Islands and the Antarctic Peninsula, and bordered on

the west by Drake Passage.

Named in about 1932 after the Scotia, the expedition ship used in these waters by the Scottish National

Antarctic Expedition (1902–04) under William S. Bruce.

The most famous traverse of this frigid sea was made in 1916 by Sir Ernest Shackleton and four others

in the adapted lifeboat James Caird when they left Elephant Island and reached South Georgia two weeks

later.

Visiting The Scotia Sea

April 2011

|

|||||

It take's about 3 days, crossing the Scotia Sea up to South Georgia.

During the first night the sea calmed down and made things a little more comfortable for us, even though

there was a long, rolling swell.

In the middle of the second day the wind direction changed and, when it started to blow from behind us,

increased the ship’s speed by just over 1 knot.

So after all this was not the most haviest part of our journey.

On our way, i have seen quite a lot of birds and a very good vieuw off the Hourglass Dolphins.